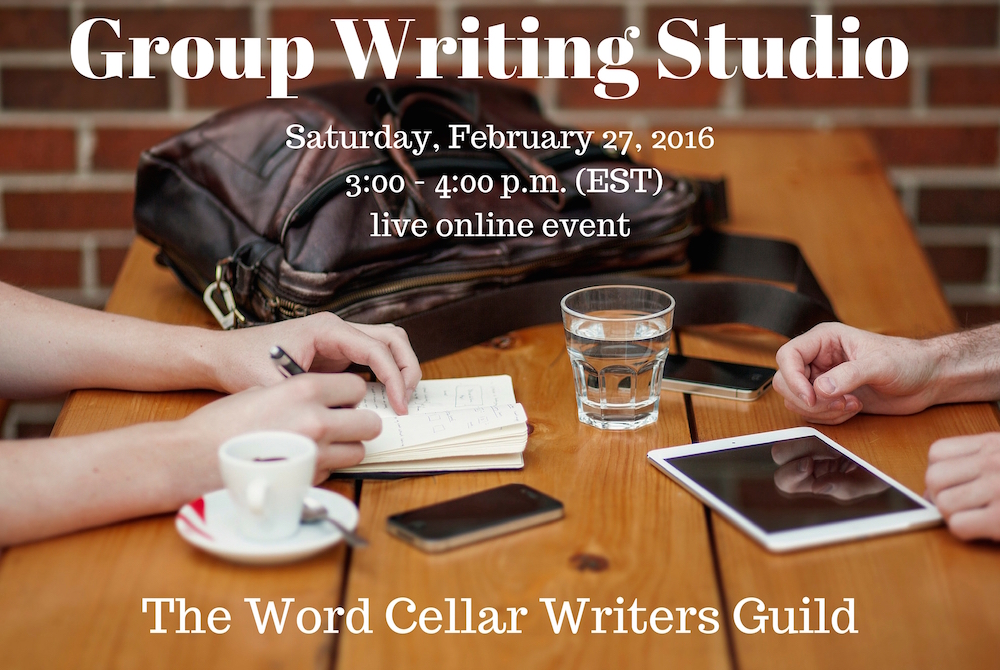

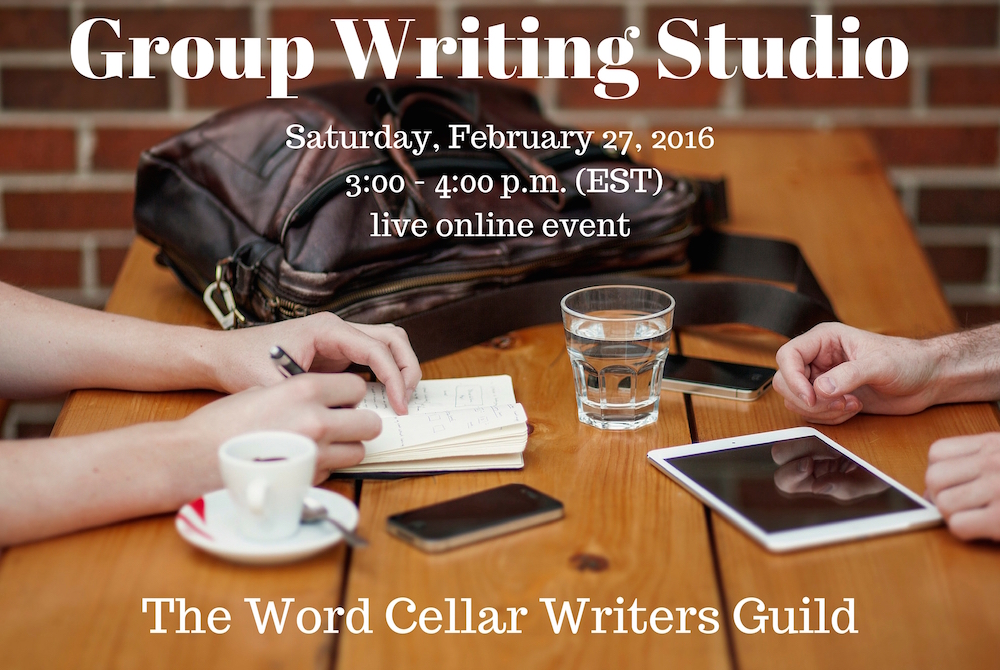

Each month in The Word Cellar Writers Guild we have at least one live, virtual event. This month, we're having Group Writing Studios. We gather via video chat for an hour to spend time writing "alone together." Each session includes a warm-up exercise, time to write quietly, and time to share (as you like).

It was such fun that I thought I'd open up the next one to anyone who wants to join us.

Group Writing Studio in The Word Cellar Writers Guild

Date: Saturday, February 27, 2016

Time: 3:00 - 4:00 p.m. (EST)

Online: Via Skype (include your Skype name in the "notes to seller")

Cost: $5 (or free for Guild members)

Making time to actually write is one of my biggest challenges, and I know many of you share that struggle. These community writing sessions are an opportunity to come together and overcome our procrastination, fear, and excuses. We put our butts in our chairs, we put some words down on paper — and we feel better for having written!

In today's session, our warm-up prompt came from Ursula K. LeGuin's book Steering the Craft: A 21st Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story. The first chapter of the book is all about the sound of your writing, and she calls this exercise "Being Gorgeous:"

"Write a paragraph to a page of narrative that's meant to be read aloud. Use onomatopoeia, alliteration, repetition, rhythmic effects, made-up words or names, dialect -- any kind of sound effects you like -- but NOT rhyme or meter."

LeGuin emphasizes that the point of this exercise is to "write for pleasure -- to play. Just listen to the sounds and rhythms of the sentences you write and play with them, like a kid with a kazoo. This isn't 'free writing,' but it's similar in that you're relaxing control: you're encouraging the words themselves -- the sounds of them, the beats and echoes -- to lead you on."

I tend to do this naturally in my writing. I'm usually acutely aware of the sounds and rhythms of my sentences, if not in the first draft, at least by the first revision. But not everyone writes that way. Some people are more keenly aware of other parts of the craft, such as the narrative arc or plot. Every writer has her own strengths and natural inclinations. The goal, I suppose, is to bring it all together at some point. (And that point is almost never the first draft.)

I wrote a few paragraphs using the "Being Gorgeous" exercise. It's not the most beautiful or profound thing I've ever written, and it's not even particularly playful. It ends up being rather dark, which is fine, becuase the last few months have been a bit dark and twisty for me. I didn't set out to write about that, though. I wasn't sure what to write, so I just started with what was in front of me: an English muffin. As you'll see, the topic immediately morphed into something else. I thought I'd share it here as an example of how one thing can lead to another, and how a writing exercise or first draft can just be what it is: practice.

"Being Gorgeous" writing exercise, rough draft:

Toast crunchy with chunky peanut butter -- all the texture you can handle before noon. Let's face it, you don't handle much before noon. No one else is quite the nightowl youa re. You weren't made for mornings with their shiny new-day-hope, their blank slate sunrises.no, you carry things with you into the dark, dragging everything along from the blue hour of twilight to the blanket of night. Other people sleep in soft beds. Your bed is soft. Your partner snores beside you. And there you are: too much of nerves and memory to fall asleep. It's not insomnia exactly, is it? You sleep eight hours or more you just do it in a time shift, always five to six hours behind the rest of your timezone. You shut down the West Coast from your home in the East. You watch New Zealanders post their after-work cocktails on Instagram. You wish you could join them for chips and salsa. You would happily join the Brits for breakfast tea. Anything to skip over the interminable wait to just fall asleep already.

And yet even this run-of-the-mill not-quite-insomnia is preferable to the fear of sleep that gripped you in your darkest hours. Then, all day was dark. Your circadian rhythm and your nerves were shot. You existed in a haze of half light, not eating, not sleeping, not really even awake. Or maybe you were too awake, a tingling network of nerves, all fear and fear. Something had broken apart inside of you, as though your body and your spirit were disconnected, a breakdown of communication between the two, trapping you inside of yourself. Your body a wild horse. Your spirit-rider terrified to get back in the saddle. You lay down to sleep and you bucked yourself awake at any little sound, even of your own breathing.

I hope you'll join us for the next Group Writing Studio on Saturday, Feb. 27.

To be part of it, you can become a member of The Word Cellar Writers Guild, or just sign up for the event.

Tuesday, May 3, 2016 at 3:39PM

Tuesday, May 3, 2016 at 3:39PM